At GDC this year, I presented a talk on applying playgrounds to multiplayer level design. Because this was a short talk, I focused on the application to level geometry and the consequences on multiplayer systems.

If you’ve followed my blog for the last few years, you’ll know my interest in playgrounds is not new. They are a metaphor I’ve used several times as an example of how digital games should adapt to their to players’ needs. What follows is my framework for these ideas in multiplayer level design. There are still many areas to explore in this space, some of which I outline along the way, but I hope this introduction to the playground metaphor helps you in your own explorations.

The Basics

Playgrounds are persistent community spaces for non-prescriptive play.

A playground is not an obstacle course to complete, a puzzle to solve, or a story to hear. There are aspects of obstacle courses and stories, but they are not consumed through player interaction; they persist. A good playground facilitates many obstacle courses, many stories, and many forms of play.

Playgrounds are places to be, not levels to beat.

Playgrounds are Multiplayer

Playgrounds are fundamentally multiplayer spaces. They support a wide range of player needs, and they scale along game mode, player count, and player trust.

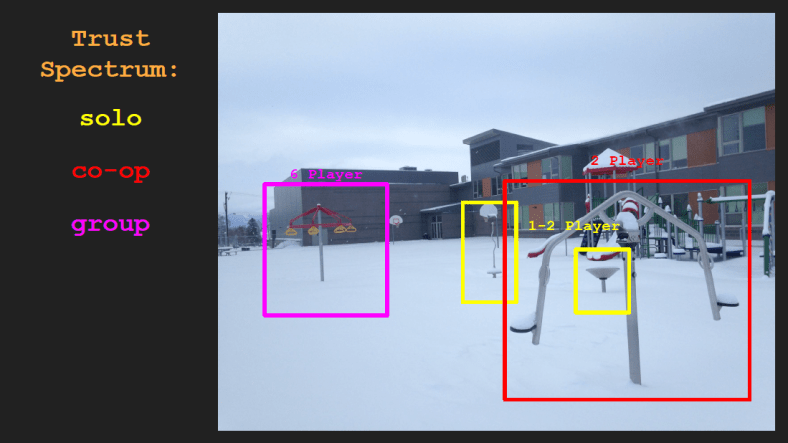

Raph Koster and a team with google explored the idea of a Trust Spectrum in games. The idea is that different multiplayer activities call for different amounts of trust, which can create barriers for an audience. If a game supports basic parallel play alongside intense, cooperative raids, there is not a path for new players to build the trust they need for the harder activities.

Playgrounds also support a trust spectrum with a range of play, from solo and parallel activities up to group competitive and cooperative play. As multiplayer spaces, playgrounds also follow some design patterns for building friendship. The activities encourage proximity and reciprocity between players.

Here, for example, are several activities as part of a playground. Players can enjoy some activities alone, or in parallel. Other activities require multiple players, some with turn-taking, others with players working together, which means reciprocal loops that build trust. These activities also don’t lock players in for long; a player can stop in the middle of an activity, or at the end of turn to opt out of play.

When I describe playgrounds as community spaces, I also mean more than the play structures. The community space includes the surrounding park, the walking paths, and benches. Playgrounds include spaces for parents to sit and talk while their children play. This is an area I want to explore further in video games, but what could serve the function of a park bench in our multiplayer game systems?

Playgrounds, Not Sandboxes

There is some overlap between playgrounds and sandboxes worth clarifying. For me, a sandbox is a neutral space where players bring toys. In contrast, a playground is the toy. Sandboxes are also used up through the act of play; often a player will need to start a new game for the sandbox to reset. The main overlap between these terms is that both allow non-prescriptive play. That is, sandbox and playground design both let the players do what they want instead of forcing one way to play.

Sandboxes best support solo and parallel play, but not rich cooperative or competitive experiences. This may be a consequence of genre convention more than a necessity. When I say that sandboxes are neutral spaces where players bring toys, I mean the individual player’s upgrade trees, loadouts, and equipment. Because these are not shared, or passed between players in turns, the game systems encourage each player to specialize in a way that may conflict with deeper cooperative play.

For example, in Saints Row IV there are a finite number of activities and collectibles in the world, and the act of play depletes this world of its potential. While exploring the world cooperatively, there are few activities that require both players. As we level up, we can each choose to spend our skill points differently. If I focus on enhancing my character’s movement abilities, while you focus on combat, then the systems are pushing us away from cooperation. You won’t be able to catch up with me while I scale the buildings, and I won’t be able to fight alongside you when you attack harder enemies. Again, the emphasis of the sandbox design is on the toys—skill upgrades in this case—that each of us collect and bring to the neutral space, instead of the space being a persistent toy for both of us to share.

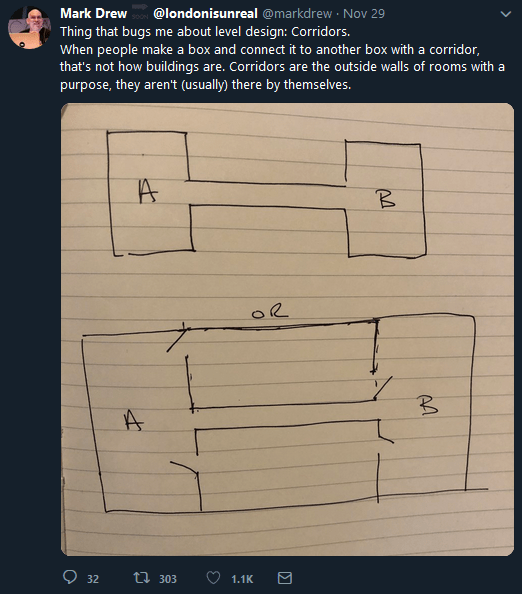

My focus with this post is on level geometry, but the way we shape our levels affects multiplayer systems. If we play Deathmatch on a King of the Hill map, the game may still play like King of the Hill. This is because level geometry and game systems work together to create the play experience.

The Formula

Now let’s dig into some examples:

Here is a basic playground from my neighborhood. If you live in North America, you are probably familiar with playgrounds like this. As playgrounds go, this one is simple and unremarkable. Importantly, we can’t convert this structure directly to our video game levels, and we wouldn’t want to, but there are lesson we can take from its design.

The basic unit of a playground is a module, a self contained chunk.

At the center of the module is a platform elevated off the ground. This playground is for young kids, so remember this platform is a meaningful vantage point for a five year old. This means it functions as a goal for that player to attain.

In order to reach the platform (the goal) the player must pass a skill check. Here that skill check is a staircase. Importantly, a good skill check is not a binary pass or fail. The player can fail and trip on the stairs, but most use falls into a range of skill: for the three year old, slow; for the five year old, OK; for the ten year old, maybe two steps at a time?

Remember the multiplayer context for these skill checks. If I can take the stairs two at a time in a game of tag, and another player can’t, then there is a tactic I can exploit around the playground.

On reaching the platform, there are routes back down that function as rewards. Here they take the form of slides, which are also opportunities for subversive play for the skilled player who will risk running up the slide. Subversive play is whenever the player thinks they are using a constraint of the design against its intent. We can design with some subversion in mind, but the flexible form of playgrounds should allow for more subversive play than we can predict.

Against the bars at the back of the platform, there is a steering wheel. This functions as a setpiece, which landmarks and differentiates modules from each other. In playgrounds, a good setpiece can also spark imagination and encourage roleplaying. (For now, the aesthetic and thematic solutions to the playground formula is a problem to save for another time.)

Now that we have a formula, we can create more complex forms. This playground is more interesting than the first example because it connects multiple modules into a complex structure.

Here we have a hierarchy, or tree. This makes a fun playground, but there is still a problem in the lack of cycles or loops. If we played tag on this structure, the only ways to go from one end to the other are by backtracking or by running on the ground. But with our abstract language of modules, we can imagine variants that do connect as cycles. With these formulas, we can now imagine infinite, sprawling playgrounds if we want!

But our imaginary playgrounds do hit a constraint of safety. Real playgrounds are safe environments for failure, where the design limits risk. Playgrounds also limit the time to recover from a failure. If I lose my grip while crossing the monkey bars, I lose a few seconds of progress before I can try again. In games, if the player fails a skill check and cannot recover in a short amount of time, then the level lacks the safety of a playground. If the player reloads a save state, we’ve designed something where recovery is too difficult. This may limit how big a playground can be and what systems we can use.

Applying the Formula to Level Design

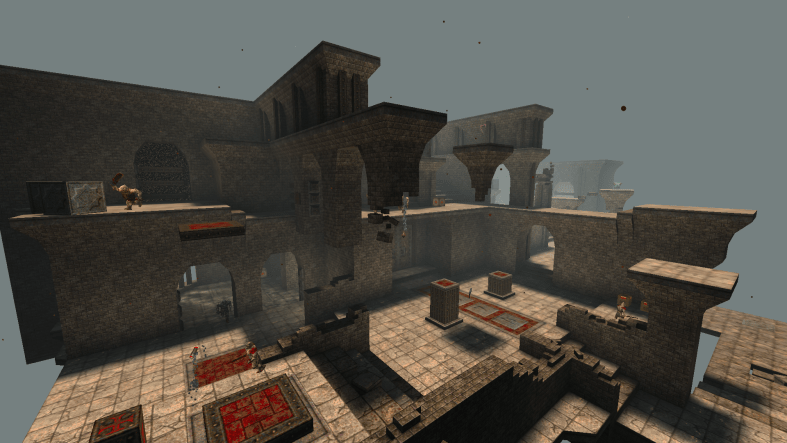

For most of my experiments with playground level design, I’ve used Quake. The most direct application of playgrounds requires a robust set of skills, which Quake has. A staircase in Quake is not a meaningful skill check, but once we add a monster at the top, there is some skill involved.

Another benefit of testing these ideas in Quake is that all levels support singleplayer, co-op, and competitive play. Once we adapt the level geometry, we’re close to my definition of playgrounds.

There are also many ways to create timing-based skill checks around moving obstacles, traps, and dynamic cover. For a game two decades old, there is a lot we can do!

Quake also has advanced movement skills:

Bunny hopping lets players maintain their momentum, and circle jumping (curving their aim while strafing in air) lets players accelerate and curve around obstacles.

Jumping at the peak of a ramp gives players more height than normal. Jumping a little too early or a little too late will still give some bonus to the jump height, which makes ramp jumps one of the easier movement skills to use.

Rocket jumping grants even more height, but it comes at the cost of some health. We also usually reserve the rocket launcher as a rare reward item.

These advanced skills create opportunities to move through the level quickly and take shortcuts, but if we made them necessary skill checks, the level would be inaccessible for most of our players. That is, these advanced skills should be fast routes and opportunities for subversive play, not the only routes.

Putting it all Together

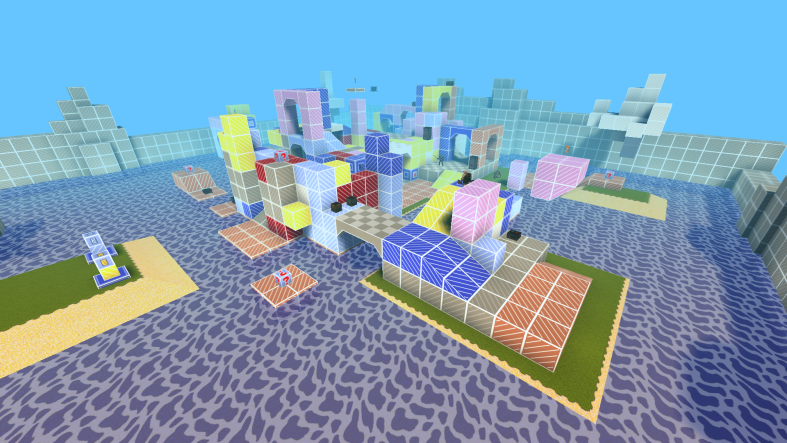

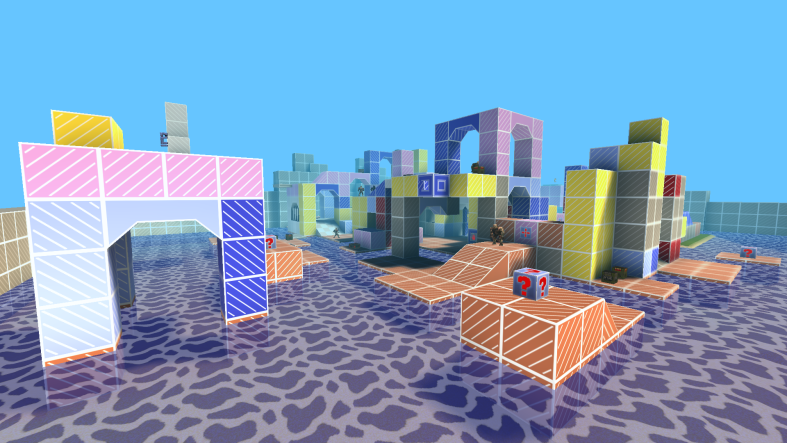

Putting these ideas together, we get a basic playground. This level plays in a different way than a standard Quake level, and I want my players to recognize this the moment they enter the map so they won’t rely on existing habits.

If we break the structure into its modules and their connecting skill checks, this should look familiar. With different skills involved, this same formula could describe a real playground.

Pushing these ideas further, adding more skill checks and rewards in the form of enemies and items, we get a pretty cool structure! Importantly, while there are objectives for the players to complete, there are many ways to approach them, many ways to add new goals, and many ways to play.

Speedrunning is one example of players creating a new goal on top of the intended design. In the video below, one of my playtesters routed a speedrun. Normally a first playthrough of the map takes 10 minutes, but here it takes 27 seconds. This speedrun also demonstrates the range of subversive play possible within this design.

(If you aren’t familiar with Quake, the speedrun starts by grabbing a secret Ring of Shadows, which makes the player invisible for 30 seconds. Normally, this is enough time to get an edge on combat or explore in safety, but not enough time to complete the level. Importantly, if the goal of speedrunning is set by players outside the game, then they can decide if they want to use the item. Speedrunners create their own categories and rules.)

For comparison, and a more thorough exploration of the level, here is my playthrough:

Other Applications for Playgrounds?

At this point you may be thinking “but Andrew, I’m not making that kind of game! How does this help me?” And probably what I’ve described is very different from what you’re making. But if you work with 3D level design and you follow the needs of camera, character, and controls, then playgrounds are still useful.

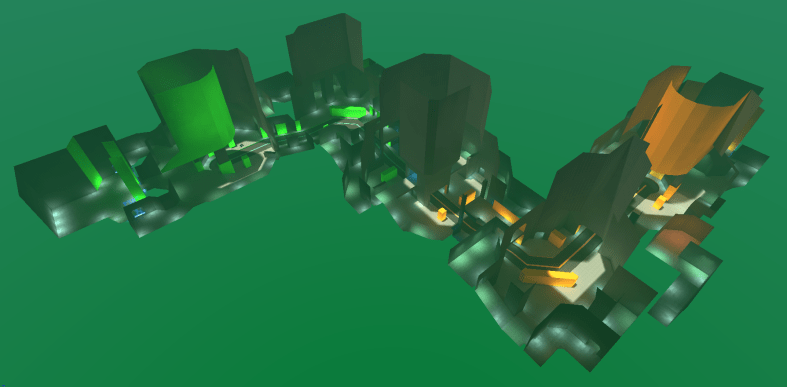

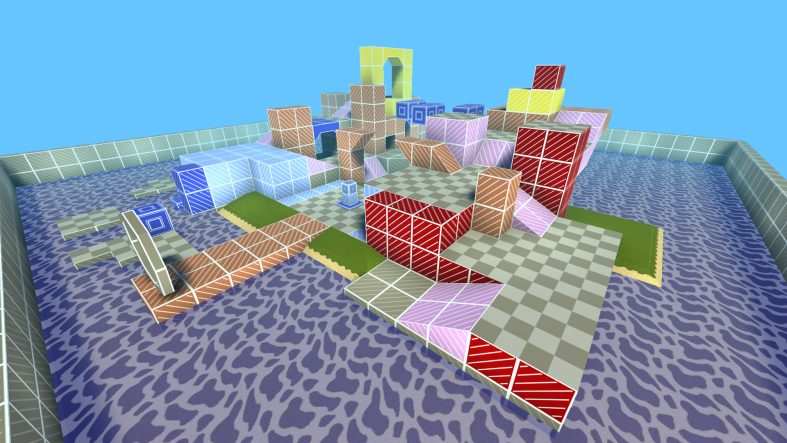

If you’re involved in prototyping or pre-production, you need metrics test maps. Normally, a metrics test map is the 3D equivalent of a meter stick to know how high, how far, how fast, and so on. But these maps can’t tell you whether your metrics are fun. So instead, metrics playgrounds!

Here’s an example of a metric playground I built to find the fundamentals of a game early in production. We had a tight third-person camera and a robust move set with double-jumping, mantling, sprinting, and crouching. In a standard metrics test map, there is no way of knowing if your character moves too fast or jumps too high. Aside from verifying your code works, distances only matter in the context of play. The purpose of my metrics playground was to provide that context.

As we continued building the game, we kept the metric playground up to date with our mechanics. We had gunplay, so there were ways to spawn enemies to shoot and others to evade. In this way, the metric playground let us test the whole game in one spot and quickly tune for fun.

Would our final levels look or play anything like these playgrounds? Probably not, and that’s OK! The purpose of the metrics playground was to find our fundamentals.

Conclusion

I am not suggesting playgrounds are a magic solution to all of our problems. Rather, playgrounds are another area of design we can study and—when appropriate to our goals—apply.

To me, playgrounds are an exciting metaphor for level design because of how they facilitate a breadth of play that we, in video games, seldom allow. They are level geometry doing the work of system design, and they show a way forward for levels that adapt to their players’ needs.

Thanks for reading,

-Andrew

(Jeff also clarified in a later tweet that his advice

(Jeff also clarified in a later tweet that his advice