Throughout the Practice 2018 design conference there was a question of building games around cooperation and negotiation. Several talks referenced the prisoner’s dilemma and its payoff matrix as a way to describe a range of outcomes for cooperation and competition. Through conversations, this problem solidified: how do we build cooperation into traditionally competitive multiplayer games? A successful solution to this problem requires cooperation and competition to both be viable and fun strategies. (Idling in a tied match until the server instance shuts down is neither). I also think these strategies should exist inside the game’s systems and mechanics instead of relying on the social dynamics that surround multiplayer games.

Fuzzy Cooperation in Battle Royales

To me these question are a response to the popularity of last-player-standing battle royale modes and the mainstream industry’s shift toward multiplayer. For the codified battle royale format, there is no cooperation in solo play. Even in squad variants, cooperation is limited to a tribal Us vs Them. These games lack mechanics to build and maintain social contracts, and there are few interactions that can benefit multiple teams. There is nothing to negotiate. At best, two teams may independently decide to keep their distance instead of fighting, or to pick on another team first.

For Player Unknown’s Battlegrounds, intentional team killing in squads and teaming up in solo play are against the rules of conduct and can be punished by a ban. There are some good reasons for this. If players were allowed to team up in solo mode, they would gain unfair advantage, which would undermine competitive play and hurt the game as an esport. In Fortnite’s code of conduct, players are told to “Play fairly and within the rules of the game”, and Epic has penalized players who team up in solo mode.

Screencap of PUBG’s Rules of Conduct

This is a significant divergence from the original inspirations for battle royale game modes. DayZ, a mod for Arma II, put its players and zombie AIs together in a huge map. Around its initial release, players were unfamiliar with the mechanics and were afraid of the zombies. As a result, those new players would signal willingness to cooperate so they could better survive. Over time, players learned the rules of the world and players formed groups. These gangs became bigger threats than the predictable zombies, which turned the game into a cruelly tribal PvP experience where kidnapping and enslavement became norms. DayZ succeeded as a multiplayer story generator, and it demonstrates both the positive and dangerously negative outcomes of fuzzy cooperation.

Another inspiration these game modes claim is the film Battle Royale about a class of students in Japan who are forced to fight to the death on an island with no escape. Unfortunately, the game modes only draw inspiration from the setting and its rules, not the social dynamics that emerge in the story. Only a few students in Battle Royale are eager to kill their classmates, and most of the students reject the rules and try to cooperate and escape. On top of being an exciting action film, Battle Royale is about generational conflict in Japan, where youth are expected to enter a competitive, zero-sum business world. The Hunger Games series falls into a similar category for a Western audience. In both of these works, the only ethical moves are to break the rules, and that gets messy when trying to survive against competitors who are acting within the immoral rules.

When I worked on a battle royale for a few months, I wanted the mode to return to its source material. In the early iterations, I had a few lofty goals (which we didn’t get to explore):

1) undermine competitive play in favor of generating unique stories. Surprise and uncertainty are the best tools for generating stories in multiplayer, and they comes at the cost of fair competition. This also means keeping the game accessible for new players by limiting the skill ceiling and going wide with systems instead of deep.

2) create ways for players to break the rules of the battle royale. My hope was to include some improbable system for a cooperative victory. (My example for this idea was to randomly spawn a “One Ring” that players could destroy in “Mount Doom” on the far side of the map.) This goal of breakable rules also means encouraging dynamic teams where cooperation and betrayal are both valid play.

3) keep death meaningful. A dead player shouldn’t back out to the menu and launch a new match as though they were respawning in an arena FPS. They should feel investment in the story of their teammates and the world. Even a defeat should feel like a complete story.

I think one key to hitting these goals is to add improbable systems for players to revive their fallen allies. One version of this system would be a “graveyard” that teams must reach and fight over to revive their friend. A more forgiving version would be like Left 4 Dead’s closets or Spelunky’s co-op coffins, where each new level section offers a chance to “rescue” a dead teammate, at some risk. Spelunky’s co-op mode also keeps dead players involved by letting them fly around as ghosts and nudge objects in the environment. The importance of these mechanics is to keep dead players invested in the game and to affect the team’s story instead of encouraging them to quit to the menu.

All of these ideas have problems to solve in the specifics of their implementation. My larger hypothesis—that cooperative story generation should take priority to fair competition—may also be false (which is to say, it may serve too small of an audience to be viable as an online game). That said, as designers who have codified the battle royale mode, I feel we have failed our source material by prohibiting cooperation and embracing a zero-sum design.

Fuzzy Cooperation Inside the Mechanics

My examples of cooperation in existing battle royales rely on external social mechanics and rules of conduct rather than mechanics built into the game. For a version of this interaction that plays through mechanics, I want to look at the MOBA formula.

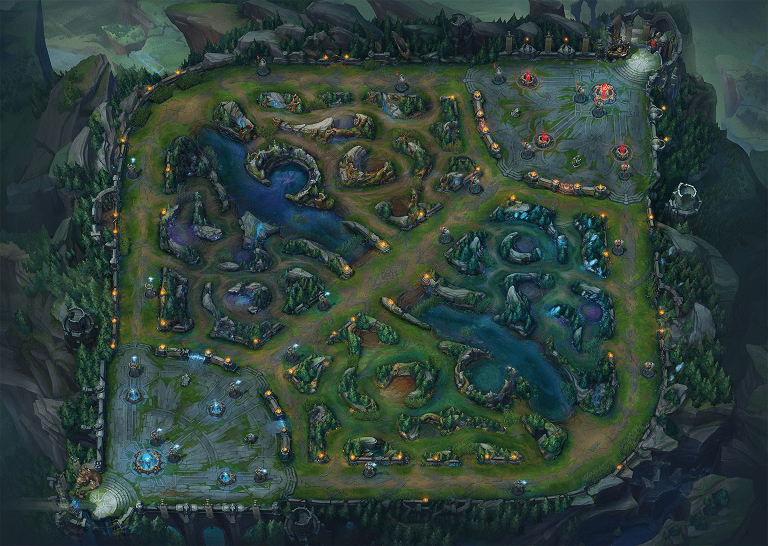

For readers who aren’t familiar, the traditional MOBA has two teams of 5 that respawn at bases on opposite sides of a 3-lane map. Each team has towers that protect their lanes from waves of AI that spawn at their opponent’s base. There are also neutral AI in areas between the lanes that players can fight over to gain resources. A player spends their resources to improve their character. Each character is unique and may have different resource needs as the match progresses. Destroying the enemy base wins the match. Beyond this, a lot varies between titles. The complexity of MOBAs makes many strategies viable, and there are ways for teams to adapt and exchange resources to get ahead.

Summoner’s Rift from League of Legends

For a prisoner’s dilemma MOBA modification, we could start with the same foundation. We would keep the two teams of 5 with their own bases that can be destroyed. We would also keep the idea of players gaining resources to improve their characters. However, instead of team AI spawning in waves to attack the opposing team, the AI would be an antagonistic third party that would spawn to the side and attack both teams. This AI team would scale in difficulty over time so that the players are pressured to gather resources efficiently. The longer a team survives, the more points they earn, and the final score would go to a leaderboard. If one team decided to steal resource from the other, they may survive longer and thus “win” the match, but they will score lower on the leaderboard than teams who cooperated. The variety of resource needs for each team should also be asymmetrical so that “trade” or “resource gathering permission” emerge in gameplay.

If players violate the peace by stealing from the other team or attacking, there need to be non-verbal tools for negotiation. A robust emote system to signal intent may suffice, but a global chat system could make cooperation too easy and introduce other problems.

While I believe this is a solution to the design problem, there are other faults. First, in this design, a “win-win” solution is still a “defeat”. Second, the mechanics are now too strict for generating a wider range of stories. As a result of these problems, I expect the game would have trouble retaining a playerbase.

Fuzzy Cooperation, but Cozy?

Another path to explore in the overlap of cooperation and competition is the idea of “cozy” design. In 2017, one Project Horseshoe report explored what it means to make a cozy game, and related research has looked into design patterns for friendship and the spectrum of player trust. To achieve the goals of these models, any competitive mechanic that can violate trust may come at too great a cost. It seems that this means swinging to the opposite side by adding competition into a cooperative game. But I think there is a way to add cozy cooperation as a subversive element within competitive games.

My early intuition here is to add features that function as “community gardens” do in real neighborhoods. Interactions with these “gardens” would persist across many multiplayer interactions and benefit other players. The garden would be a medium for giving gifts to the community, and for player expression.

An easier implementation: add toys to a competitive environment. Add a big trampoline in the middle, add a fishing pond, add a slip’n’slide. Let players opt out of competitive play if they want, and give them the tools to do so.

Other Examples?

I’ve had my head down in traditional multiplayer design, and I know I’m blind to some of the work going on in this space. However, there are a few recent examples that come to mind:

- Destiny 2 is adding a new game mode called “Gambit” where two teams fight separate waves of enemies and have opportunities to invade the other team. This sounds like a horde mode with a little competitive play added in, but well have to see how it plays out.

- Fallout 76 is online with a shared, persistent world of a dozen or so players. It is not strictly competitive or cooperative. It is also not clear how the game will police uncooperative behavior, or if it will have the same problems as Ultima Online.

- One Hour One Life is a shared world multiplayer game by Jason Rohrer where players try to advance technology by working on the civilizations that outlive their characters.

Conclusion

There is potential for us to reach new audiences and tell new stories by moving away from traditional competition. As a multiplayer designer, I want to create better shared experiences (and create fewer experiences that encourage toxicity and hate). I think there is potential to achieve these goals in games designed around fuzzy cooperation and negotiation. There are also many problems to solve, but I hope this post has been a useful step forward.

Thanks for reading!

References:

All sources were retrieved July 4th, 2018

- Player Unknown’s Battlegrounds Rule of Conduct https://www.pubg.com/rules-of-conduct/

- Fortnite Code of Conduct https://www.epicgames.com/fortnite/en-US/news/fortnite-code-of-conduct

- PCGamesN “Epic Will Ban You if You’re Caught Teaming Up In Fortnite Solos” https://www.pcgamesn.com/fortnite/fortnite-squads-solo-matchmaking

- Kotaku “DayZ Player Sings and Plays Guitar for His Life” https://steamed.kotaku.com/dayz-player-sings-and-plays-guitar-for-his-life-1693226685

- Project Horseshoe “Coziness in Games: An Exploration of Safety, Softness, and Satisfied Needs” https://www.projecthorseshoe.com/reports/featured/ph17r3.htm

- Raph Koster “The Trust Spectrum” https://www.raphkoster.com/2018/03/16/the-trust-spectrum/

- Raph Koster “A Brief History of Murder in Ultima Online” https://gamasutra.com/blogs/RaphKoster/20180627/320893/A_brief_history_of_murder_in_Ultima_Online.php